Now Playing: Shamanism

Topic: The Shaman

Rolling Thunder/A practicing Shaman

A Native American Indian medicine man, spiritual leader, philosopher, and acknowledged spokesman and intertribal shaman for the Cherokee and Shoshone tribes, Rolling Thunder, served as a consultant to the popular films Billy Jack (1971), and its sequel, Billy Jack II (1972). His way of life as a powerful healer, teacher, and activist gave him widespread fame following the films. Internationally known, Rolling Thunder's spiritual counsel and tribal skills were sought on a regular basis by many in the entertainment industry.

Rolling Thunder was among the first ever to be studied by mainstream institutions and undergo many laboratory tests to determine the authenticity of his shamanic skills. It had been said that his powers over the elements of nature surpassed any seen in recent times. Reports of Rolling Thunder's ability to "make rain" on a clear day, to heal disease and wounds, to transport or teleport objects through the air, and his telepathic skills were legendary until he agreed to submit himself to testing. His abilities have been investigated and documented by such organizations as the Menninger Foundation.

An advocate for Native American rights, as well as for ecological harmony, Rolling Thunder traveled widely and was in great demand worldwide for his insight and teachings. He himself joked that he had to make it rain and thunder "in order to clean the polluted air" before he spoke in a new city. Speaking before spiritual, ecological, psychological, and healing gatherings, Rolling Thunder participated in conferences sponsored by the Association for Research and Enlightenment (Edgar Cayce's Foundation), the Menninger Foundation, the East West Academy of the Healing Arts, the Stockholm United Nations Conference on the Environment, the World Conference of Spiritual Leaders of the United Nations, and the World Humanity Conference in Vancouver, B.C., among others.

Often controversial, and regarded even militant at times, Rolling Thunder was known for being outspoken and "telling it like it is." "The Great Spirit guides me to tell people what they need to know, not what they want to know," he often said. Never making claims for his special powers, he reminded those who called him a medicine man, or who spoke of his healing abilities, that "All power belongs to the Great Spirit." Then he would add, "You call him God." In response to the charges of being militant, Rolling Thunder said, "Yes, I'm a militant. So was your great healer they call Jesus Christ."

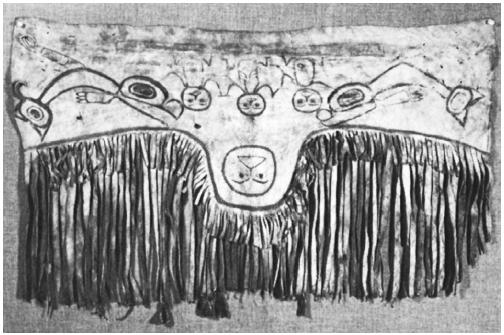

A shaman's headdress (depicted upside down)

A shaman is one who serves his people by acting as an intermediary to the spirit world. The claimed ability to communicate with the world beyond death is at least as old as the time when early humans first conceived the idea that some part of them somehow survived physical death and existed in some other place in spirit form.

The grief that came with the sorrowful thought of losing all contact with a loved one was lessened by the assertion of a fellow tribesperson that he or she could still communicate with the spirit of the one who lay in the grave. Among early humans, those individuals who claimed to be able to visit the place of the dead were known as shamans, and the messages that they relayed from the spirit world were sought by the elders regarding every major tribal decision.

Originally, the term "shaman" was applied to the spirit doctors and exorcists of the Tungus of Siberia, but in recent years the title has been applied as well to the medicine men and women of the various North American tribes who also serve as mediums, healers, and visionaries for their people. Many tribal traditionalists still revere the wisdom that is shared by those men and women who maintain the shamanic traditions and who travel to the other side in the company of their spirit helper.

In the introduction to his book The Way of the Shaman (1982) anthropologist Michael Harner writes that shamans "…whom we in the 'civilized' world have called 'medicine men' and 'witchdoctors' are the keepers of a remarkable body of ancient techniques that they use to achieve and maintain well-being and healing for themselves and members of their communities." Harner states that shamanic methods are remarkably similar throughout the world, "even for those peoples whose cultures are quite different in other respects, and who have been separated by oceans and continents for tens of thousands of years."

The anthropologist Ivar Lissner, who spent a great deal of time among the Tungus of Siberia, as well as native peoples in North America, defines a shaman as one "…who knows how to deal with spirits and influence them.…The essential characteristic of the shaman is his excitement, his ecstasy and trancelike condition.…The elements which constitute this ecstasy are a form of self-severance from mundane existence, a state of heightened sensibility, and spiritual awareness.

The shaman loses outward consciousness and becomes inspired or enraptured. While in this state of enthusiasm, he sees dreamlike apparitions, hears voices, and receives visions of truth. More than that, his soul sometimes leaves his body to go wandering."

It is believed that during those times when the souls of shamans go wandering, they project their consciousness to faraway places on Earth as well as to the shadow world of spirits.

These soul journeys may inform those who seek their shaman's counsel of everything from where to find the choicest herds of game to how to banish a troublesome spirit from their home. Those men and women who aspire to learning such techniques for themselves may pay a shamanic practitioner for the privilege of undergoing an arduous course of training that would include periods of fasting, going on vision quests, and encounters with the world of spirits—a regimen that may take the student many years to accomplish.

In 1865, the great warrior Roman Nose, who had studied under the tutelage of White Bull, an elderly Cheyenne medicine man, lay on a raft for four days in the midst of a sacred lake. Roman Nose partook of no food or water, and he suffered a relentless sun by day and a pouring rain by night. But he felt none of these distractions, for Roman Nose was in a trance so deep that he appeared to be dead.

When he returned from the Land of the Grandparents, the place of spirits, Roman Nose had obtained the necessary vision teachings to attack the white man's cavalry who were invading the Powder River country.

On the day of battle, Roman Nose mounted his white pony and told the assembled warriors not to accompany his charge until the Blue Coat soldiers had emptied their rifles at him. The power that he had received from the spirits during his "little death" had rendered him impervious to their bullets.

Roman Nose broke away from the rest of the war party and urged his pony into a run toward the ranks of white soldiers standing behind their wagons. When he was so near that he could see their faces, Roman Nose wheeled his mount and rode parallel to their ranks and their rifles.

He made three or four passes before volley after volley from the soldiers' Springfield rifles. He remained untouched, unscratched. Finally a musket ball knocked his pony out from under him, but Roman Nose rose untouched and signaled his warriors to attack. They believed that magic he had received from the spirits kept him safe that day from all the bullets.

While one can pursue the path of becoming a medicine man or woman by undergoing a vision quest, receiving a spirit guide, and serving an apprenticeship under the direction of an established medicine person, traditionally, it seems, the greatest shamans are created by spiritual intervention in the shape of a sudden and severe illness, spells of fever, epileptic seizures, or possession by tutelary spirits.

It would appear that those who become the most effective intermediaries between the worlds of flesh and spirit must have their physical bodies purged and nearly destroyed before they can establish contact with spirits.

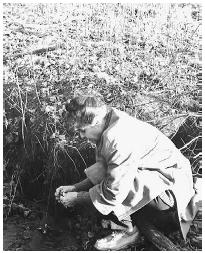

Twylzh selecting medicine Stones

Black Elk (1863–1950), the respected medicine practitioner/shaman of the Oglala Sioux, became a "hole," a port of entry for spirits to enter the physical world, when he fell terribly ill as a boy of nine. He heard voices telling him that it was time for him to receive his first great vision, and he was taken out of his body by two spirit guides who informed him that they were to take him to the land of his grandfathers. Here, in the land of the spirits, Black Elk received the great vision that was to sustain him all of his life. When he was returned to his body, his parents greeted the first flutterings of his eyelids with great joy. The boy had been lying as if dead for 12 days.

As he grew to maturity and learned to focus his healing and clairvoyant energies, Black Elk never failed to credit the other world for his accomplishments and to explain that he was but a "hole" through which the spirits entered this world. Rather than the

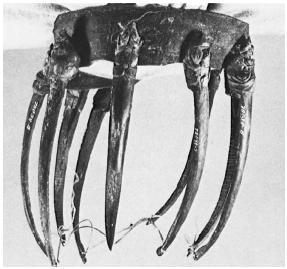

Shamans Kilt

In many tribal societies, the pseudo-death, or near-death experience, appears to be nearly a precondition that must be met by those who aspire to the role of the most prestigious of shamans.

In 1890, Jack Wilson, a Paiute who worked as a hired hand for a white rancher, came down with a terrible fever. His sickness became so bad that for three days he lay as if dead. When he returned to consciousness, he told the Paiutes who had assembled around his "corpse" that his spirit had walked with God, the Old Man, for those three days; and the Old Man had given him a powerful vision to share with the Paiute people.

His vision proclaimed that the dead of many tribes were all alive, waiting to be reborn. If the native peoples wished the buffalo to return, the grasses to grow tall, and the rivers to run clean, they must not injure anyone; they must not do harm to any living thing. They must not make war. They must lead lives of purity, cease gambling, put away strong drink, and guard themselves against all lusts of the flesh.

Jack Wilson's grandfather had been the esteemed prophet Wodziwob. His father had been the respected holy man Tavibo. Among his own people, Wilson was known as Wovoka; and now he, too, had spent his time of initiation in death and had emerged as a holy man and a prophet.

The most important part of the vision that the Great Spirit had given to Wovoka was the Ghost Dance. The Paiute prophet told his people that the dance had never been performed anywhere on Earth. It was the dance of the spirit people of the Other World. To perform this dance was to insure that the Great Mystery's blessings would be bestowed upon the tribe. Wovoka said that the Old Man had spoken to him as if he were his son and assured him that many miracles would be worked through him. The native people had received their shamanic messiah.

A crucial element in shamanism is the ability to rise above the constrictions and restraints of linear time. In his text for American Indian Ceremonial Dances (1972), John Collier comments upon the shaman's and the traditional native people's possession of a time sense that is different from the present societal understanding of the passages of minutes, hours, and days. At one time everyone possessed such freedom, Collier says, but the mechanized world took it away. If humans could exist, as the native people in their whole lives affirmed, "in a dimension of time, a reality of time—not linear, not clock-measured, clock-controlled, and clock-ended," Collier suggests that they should gladly enter it, for individuals would expand their consciousness by being there. "In solitary, mystical experience many of ourselves do enter another time dimension," he continues. But the "frown of clockwork time" demands a return to chronological time. The shaman, however, recognizes that this other time dimension originated "within the germ plasm and the organic rhythms…of moveless eternity. It is life's instinct and environment and human society's instinct and environment. To realize it or not realize it makes an enormous difference."

Achieving a deep trance state appears to be the most effective way that shamans regularly abandon linear time restrictions in order to gain entrance to that other dimension of time. By singing their special songs received in vision quests or dreams, shamans put themselves into trances that permit them to travel with their spirit helpers to the Land of the Grandparents, a place free of "clockwork time," where they gain the knowledge to predict the future, to heal, and to relay messages of wisdom from the spirit people.

Shaman's Mask

Spirit guides

When spirit mediums speak of their control or guide, they are referring to the entity from the world beyond physical death who assists them in establishing contact with deceased humans. The spirit guides of mediums usually claim to have lived as humans on Earth before the time of their death and their graduation to higher realms of being.

In the shamanic tradition, the spirit guide or spirit helper is usually received by those who choose to participate in a vision quest. Before initiates embark upon this ordeal, tribal elders and shamans tutor them for many weeks on what to expect and what is expected of them. In many shamanic traditions, the

Shaman's necklace

spirit helper serves as an ambassador from the world of spirits to the world of humans an often manifests in animal form to serve as a kind of chaperone during visits to other dimensions of reality.

For the more contemporary spirit mediums, who often prefer to call themselves "channels," the guide may represent itself as a being who once lived as a human on Earth or as a Light Being, an extraterrestrial, or even an angel. Regardless of the semantics involved, today's mediums and channels follow the basic procedures of ancient shamanic traditions.

Totem animal

Among the shamanic or medicine teachings of the traditional Native Americans, the totem animal represents the physical form of one's spirit helper, the guide, who will lead the shaman into the spirit world and return him or her safely to the physical world. Contrary to the misinterpretations of early missionaries, the native people did not worship these animal representations of their guides as gods.

Latvian ethnologist Ivar Lissner stated in his Man, God, and Magic (1961) that his 17 years of expeditions among the shamans and people of the Tungus, Polynesians, Malaysians, Australian Aborigines, Ainus, Chinese, Mongols, and North American tribes demonstrated to him quite clearly that totemism is not religion. While all these diverse people lived in a world filled with animate beings, they all believed in a single supreme deity.

Aside from a few Venus-type mother-goddess statuettes, there remains a rather strange collection of ghostly creatures and a great variety of two-legged beings with the heads of animals and birds. Why, so many anthropologists have wondered, did these cave painters, despite their remarkable artistic gifts, never pass on an accurate idea of their features? Why did they confine themselves to portraying beings that were half-human, half-animal?

And then Lissner has an inspiration. It is quite possible that the Stone-Age artists really were portraying themselves, but in something more than in human shape. Perhaps they were depicting themselves "…in the guise of intermediary beings who were stronger than common men and able to penetrate more deeply into the mysteries of fate, that unfathomable interrelationship between animals, men, and gods." Lissner suggests that what the ancient cave painters may have been relaying is that the "road to supernatural powers is easier to follow in animal shape and that spirits can only be reached with an animal's assistance." The ancient artists may have been portraying themselves after all, but in animal guise, shamanistically.

The spirit guides, appearing as totemic animals, guide the shamans to the mysterious, transcendent reality beyond the material world and lead them into another dimension of time and space wherein dwell the inhabitants of the spirit world. It is through such a portal that mediumistic shamans must pass to gain their contact with the grandfathers and grandmothers who reside there. With their spirit guide at their side in the form of a totem animal, they can communicate with the spirits and derive wisdom and knowledge which will serve their tribe or those who have come to seek specific information from the world beyond death.

Vision quest

The personal revelatory experience and the contact with the spirit world received during the vision quest becomes the fundamental guiding force in the shaman's power (medicine). In addition to those who would be shamans, all traditional young men and women may partake of the vision quest, setting out alone in the wilderness to fast, to exhaust the physical body, to pray, to establish their own contact with the dimension of spirit, and to receive their individual "medicine" power. The dogma of tribal rituals and the religious expressions of others become secondary to the guidance that one receives from his or her own personal visions.

"The seeker goes forth solitary," writes Hartley Burr Alexander in The World's Rim (1967) "carrying his pipe and with an offering of tobacco. There in the wilderness alone, he chants his song and utters his prayers while he waits, fasting, such revelation as the Powers may grant."

The vision quest is basic to all traditional Native American religious experience, but one may certainly see similarities between the youthful tribal members presenting themselves to the Great Mystery as helpless, shelterless, and humble supplicants and the initiates of other religious traditions who fast, flagellate, and prostrate themselves before their concept of a Supreme Being.

In Christianity, the questing devotees kneel before a personal deity and beseech insight from the Son of God, whom they hope to please with their example of piety and self-sacrifice.

In the Native American tribal traditions, the power granted by the vision quest comes from a vast and impersonal repository of spiritual energy; and those who partake of the quest receive their personal guardian spirit and a great vision that will grant them insight into the spiritual dimensions beyond physical reality.

For the traditional Native American, the vision quest may be likened to the first Communion in Christianity. Far from being a goal achieved, the vision quest marks the beginning of the traditionalist's lifelong search for knowledge and wisdom.

Nor are the spiritual mechanics of the vision quest ignored once the youths have established contact with their guardian spirit and with the forces that are to aid them in the shaping of their destiny. At any stressful period of their life, the traditionalists may go into the wilderness to fast and to seek insight into the particular problems that beset them.

Hartley Burr Alexander saw the continued quest for wisdom of body and mind—the search for the single essential force at the core of every thought and deed—as the perpetually accumulating elements in medicine power.

The reason the term "medicine" became applied to this life-career function is simply because those attaining stature as men and women who had acquired this special kind of wisdom were so often also great healers. The true meaning of "medicine" extends beyond the arts of healing to clairvoyance, precognition, and the control of weather elements.

The power received in the vision quest enables the practitioner to obtain personal contact with the invisible world of spirits and to pierce the sensory world of illusion which veils the Great Mystery.